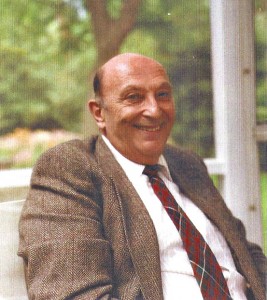

Fathers’ Day has come and gone, and I barely registered the day; my father has been dead for almost 20 years, and of course I think of him, but not any more or less on Fathers’ Day. I don’t recall making a particular fuss over him when he was alive; he didn’t really like that kind of attention. My father was a man of many contradictions, he was charming and infuriating, funny and distant, and we never managed to repair our relationship (fractured when my mother died) enough to have a single meaningful or emotionally connected conversation.

My father was a consummate storyteller. He was master of the Borscht Belt shaggy dog, had all kinds of accents in his repertoire, and though his endless puns drove our family mad, other people seemed to find them clever and endearing. I like to think I inherited—either through genetics or exposure, his gift of spinning a fine tale. I love telling jokes, and at those rare dinners when things were convivial and everyone was speaking to each other I loved to hear him tell them. I studied his delivery and timing way before I was aware I was doing so. Annie Dillard in her autobiographical An American Childhood recalled the importance of telling jokes at the family dinner table, but ours was truly my father’s venue, and we were his audience.

I remember many of his stories, yet I hardly know anything about him. He told us stories about other people; strange and quirky clients, historical figures, and distant relatives. He grew up in a family of four children, each born four years apart. He rarely talked about them or his parents; people I knew, but didn’t know much beyond my personal experience of them. Every family has some good dirt, but if my father’s family did he never mentioned it. He never told me stories or even spoke about my mother (something I was desperate for) and their life together.

The year I turned seven, my mother died, his younger sister had heart failure while giving birth to my cousin, and was revived, but never fully recovered, his father died, and not long after that my mother’s father died. Perhaps it was all more than he could bear, but that year he became someone I didn’t recognize. The man I’d spent hours playing the piano, singing, and going to the park with on Saturdays, vanished and was replaced with a stern, taciturn guy who looked a lot like my dad.

I don’t know if the changes were evident to anyone else but me. My brother was too little, and certainly, no one mentioned it. If they had it would have been in hushed, sympathetic tones ‘Poor Elliot, it must be so hard for him losing Ruthanne and having to raise those two kids alone’. And he was and was not alone; my grandmother had moved in with us, we had a full-time live-in maid, and he remarried two years later. I once tried to explain to my step-mother the changes in him, but she hadn’t known him before.

The jokes, puns, and stories were the only recognizable vestiges of his former self. It was in those moments that I’d see a glimmer of the daddy I used to know. The stories would be long and filled with detail, but he was never the hero of the tale. They didn’t offer a window into his childhood, or youth. I know he attended Erasmus Hall High School, Cornell University, NYU law school, and that he served in Korea, but I don’t know how he felt about any of it.

When I was around 20 my younger sister and I attended a wedding with our parents. I’m not sure how the topic came up, but I asked each of them if they had a do-over would they have four kids, as each of them had intentionally had two. My mom always up for a game of let’s pretend thought it over for about ten seconds and said yes; having four had been fun and she enjoyed all of us and having a big family. My father flatly refused to engage. He said there was no point in wondering, he’d ended up with four children, and couldn’t imagine anything different, and my asking or wondering was a waste of time. Despite his love of stories, fantasy and imagining felt out of the question; he wouldn’t go there.

We had cookouts on Fathers’ Day, but my dad hated cooking outside so I cooked the ribs. I’d par-cook them in simmering water, then put them on the hot charcoal grill to finish them off, not brushing on the sauce until they were almost done so it wouldn’t burn. We ate on the screened in porch. That’s what I remember about Fathers’ Day.

My father’s death meant we had run out of time to reconnect. I felt bad for my father, sorry he’d never been comfortable enough with me to get to know me. I was sorry he’d missed knowing me and at the time I didn’t think about how much of himself he’d withheld from me. There are many things I remember about my father, but when I hear other people talk about their fathers I feel a bit wistful for what we both missed.

.jpg)

Cathy Goodwin - Nice post! It sounds like your dad was very much a product of his generation. See http://nyti.ms/28Vm0Yh for a good discussion (about 1/3 of the way through the article) about how men used to deal with emotions.

nrlowell@comcast.net - He was indeed, as are we all…

Ellen - I’m so sorry for what your dad endured, and that you and he were not able to be close. My dad 25 years ago, so no Father’s Day for me either. We had been close, but at the time of his death we were estranged. It makes me sad that he never got to know my kids.

nrlowell@comcast.net - Ellen, I’m sorry for that.

Paul D. Brads - This is good, my fave de jour.

nrlowell@comcast.net - Thanks, this makes my day! Maybe even my week 🙂

Danielle Dayney - Aww, I love this. I don’t speak to my real father anymore (I’ve tried to reconnect, but have been very unsuccessful), and this makes me wish that he was a more reasonable person. I would love to pass on stories of my mom, when they were together, to my daughters. Right now, I have stories of my mom and stepdad, but there is a huge gap. My mom passed away over four years ago and I still have difficulty with that. Beautiful writing, as always.

nrlowell@comcast.net - Thanks Danielle. Families are minefields in one way or another. My motto; no one escapes childhood unscathed.

Sheila Qualls - Beautiful story. Different generation.

nrlowell@comcast.net - That seems to be the consensus. I am well aware that when I as growing up no one was particularly concerned about the psyche of children, and now the pendulum has swung…

Laura - I like how the theme of storytelling carries through – it makes the ending even more heartwrenching to see him refuse to engage in it anymore, after he taught you so much about it.

nrlowell@comcast.net - Thanks Laura. He was a man of contradictions.

Melony Boseley - Such a well written post. I was a total Daddy’s girl despite his many abhorrent flaws. Having been without him now for 9 years, it’s easy to look back at all the good he did but even easier to see the bad. My final year with him was strained at best and I am filled with regret that I never got a chance to mend that. Your words mirror mine in a lot of ways.